Environmental Transcendentalism

Kaiser is a visual artist working with photography, video, and installation. Her art practice explores the relationships between mysticism, interspecies connection, and future ecologies. Her latest work documents the slow roil of civilization vs nature.

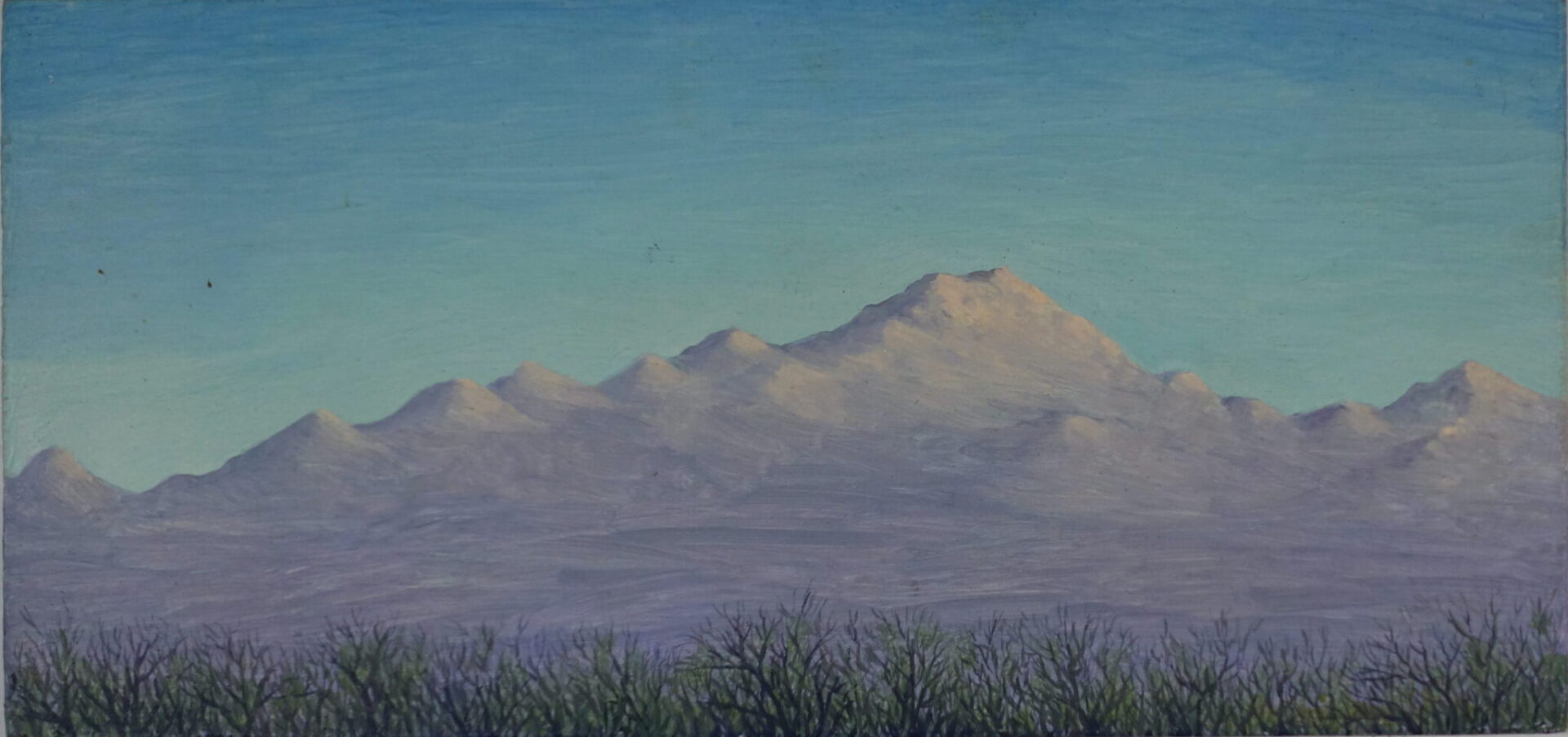

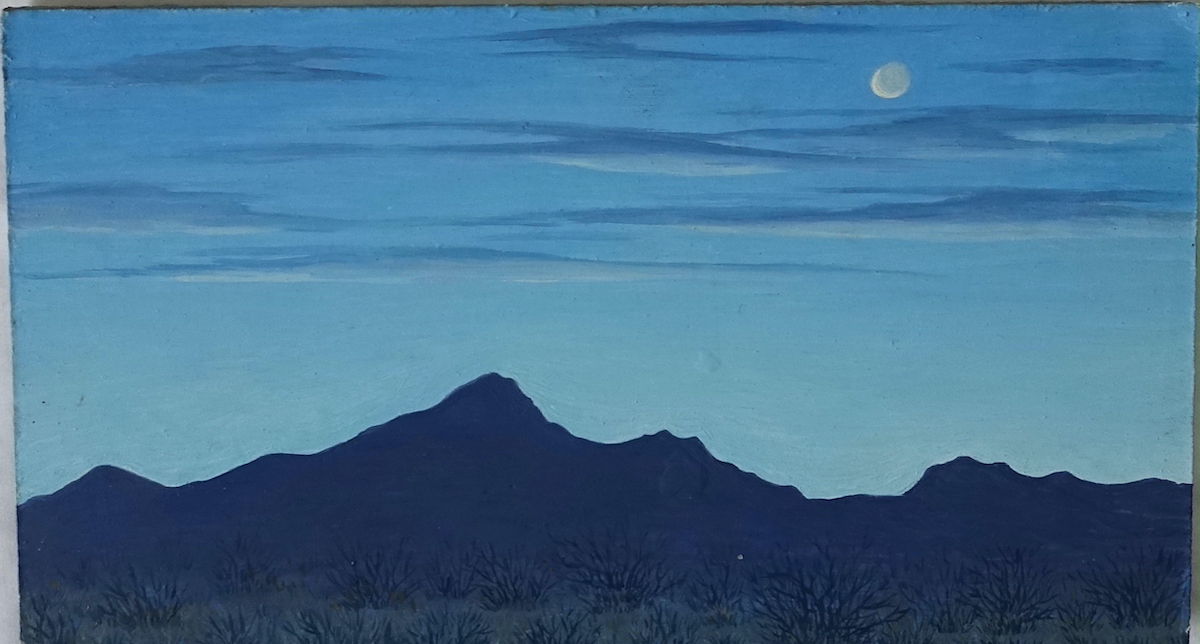

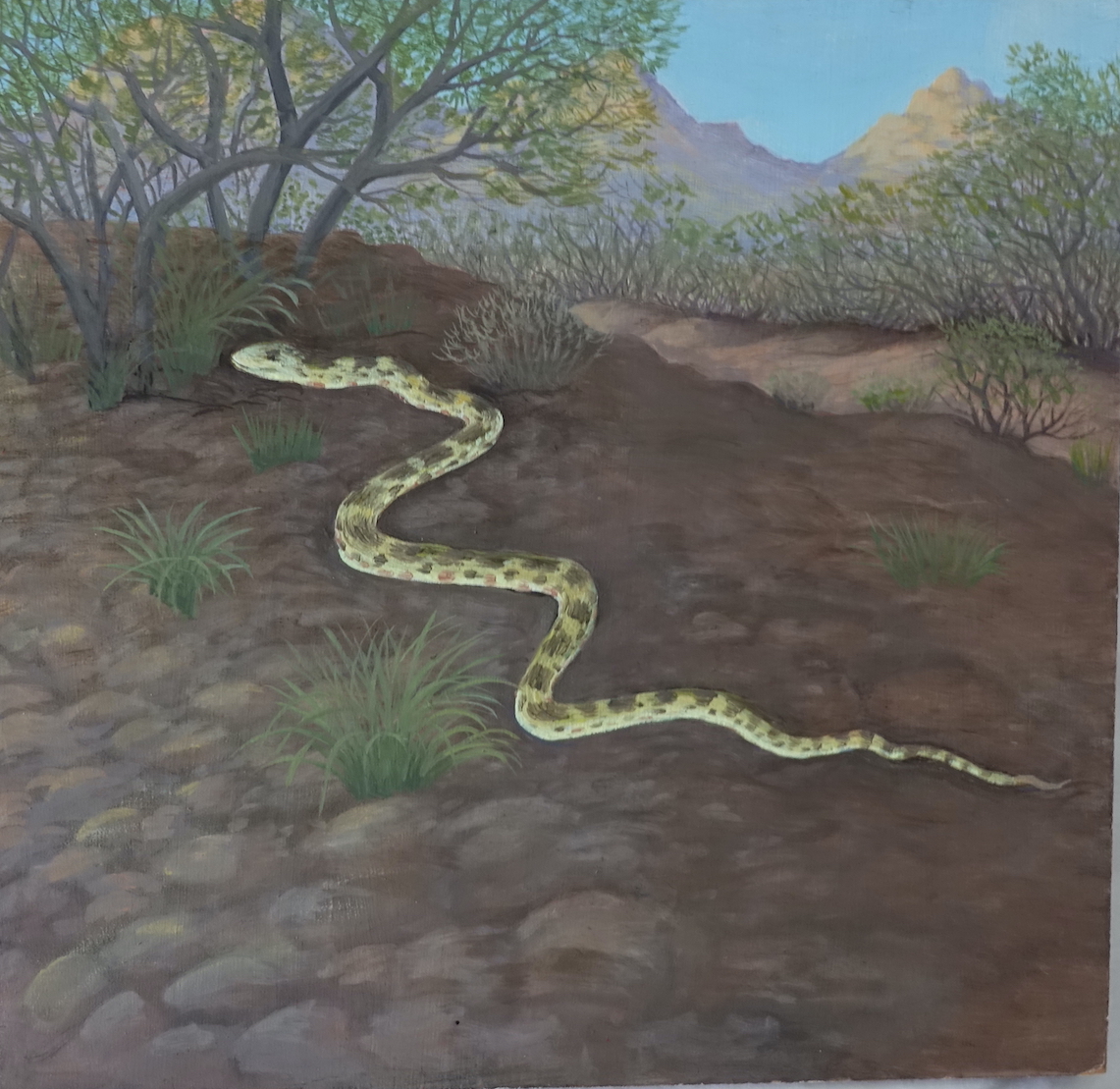

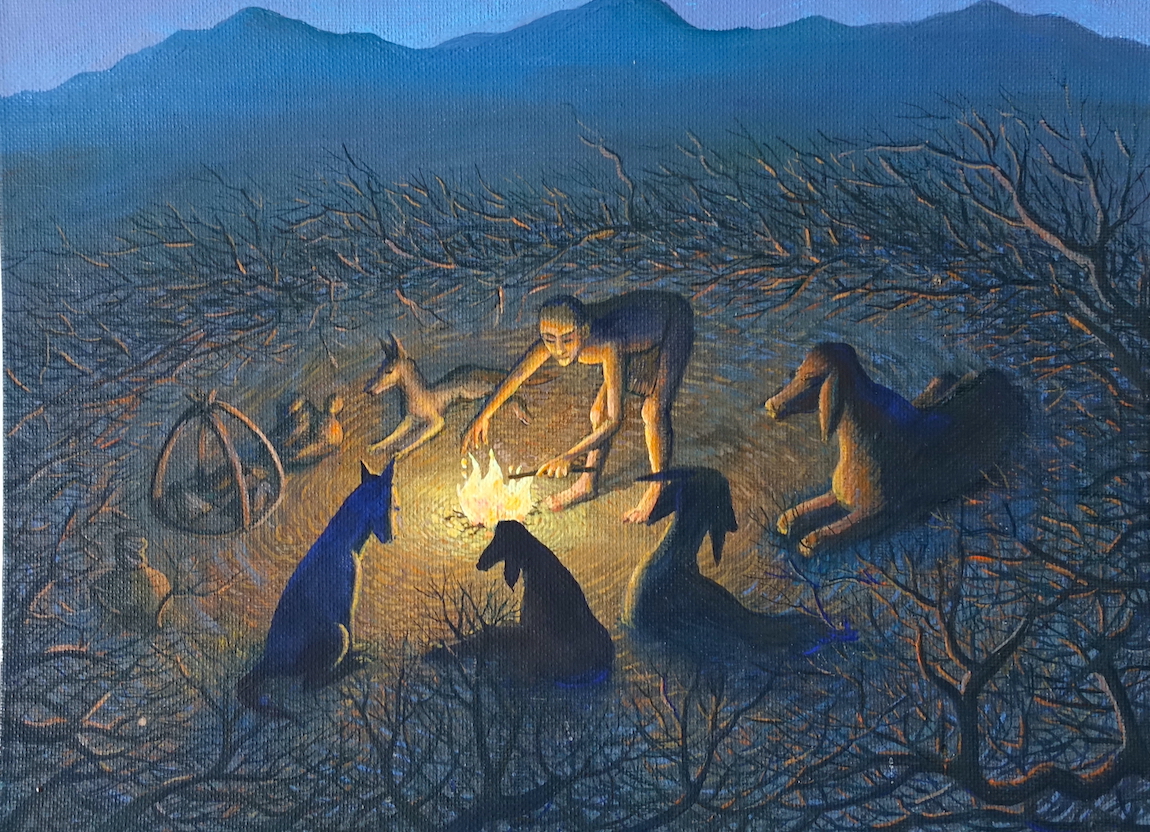

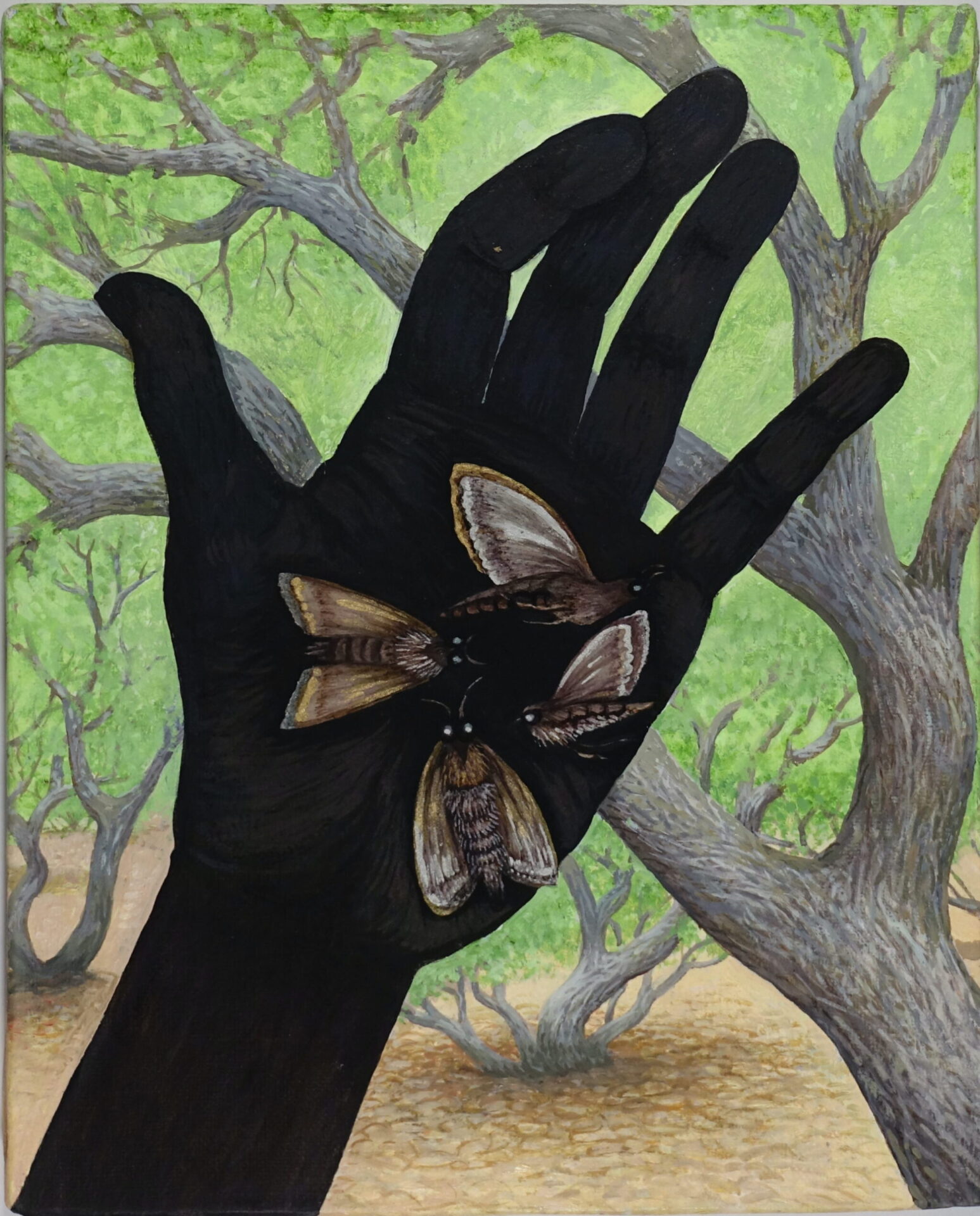

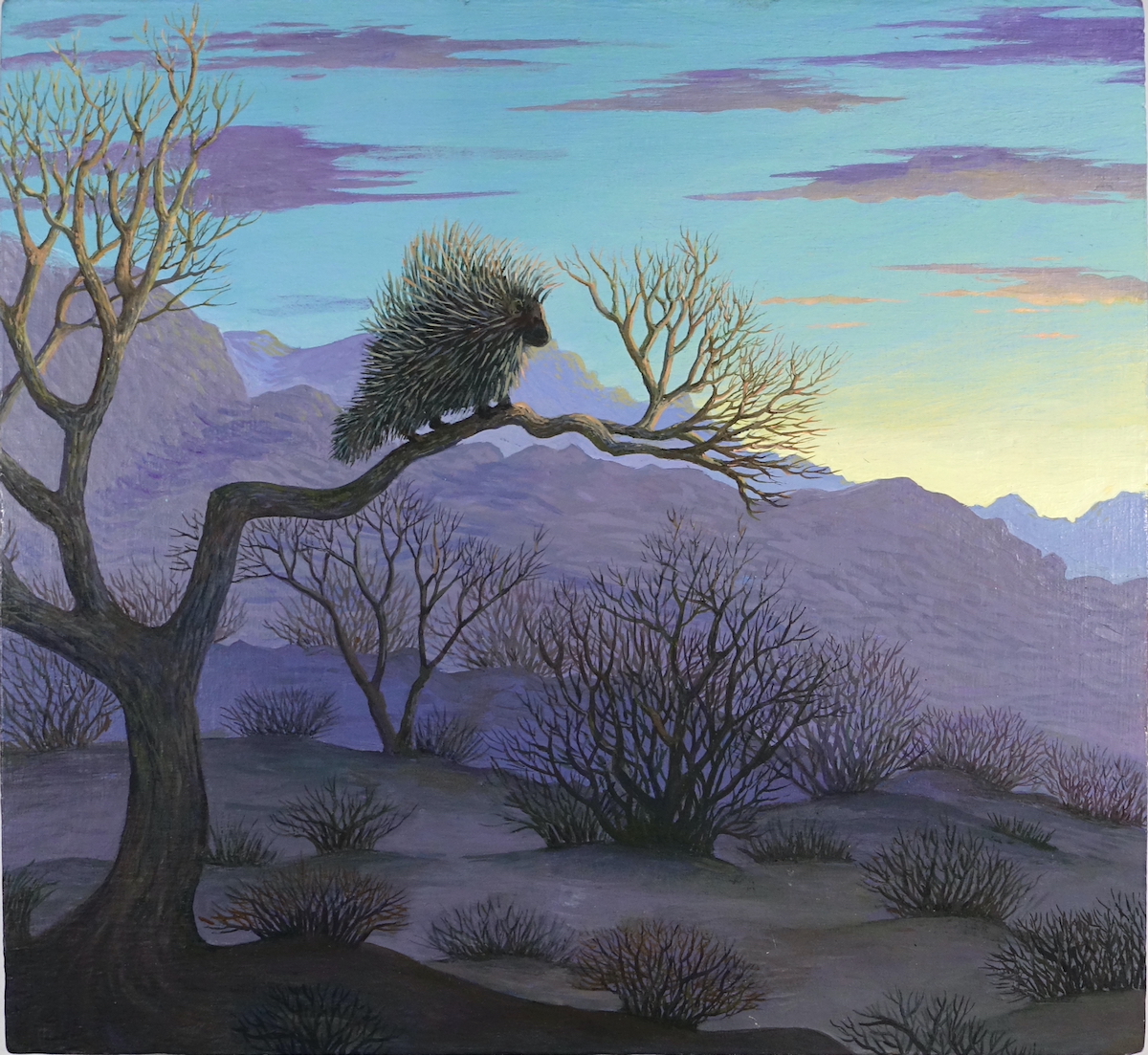

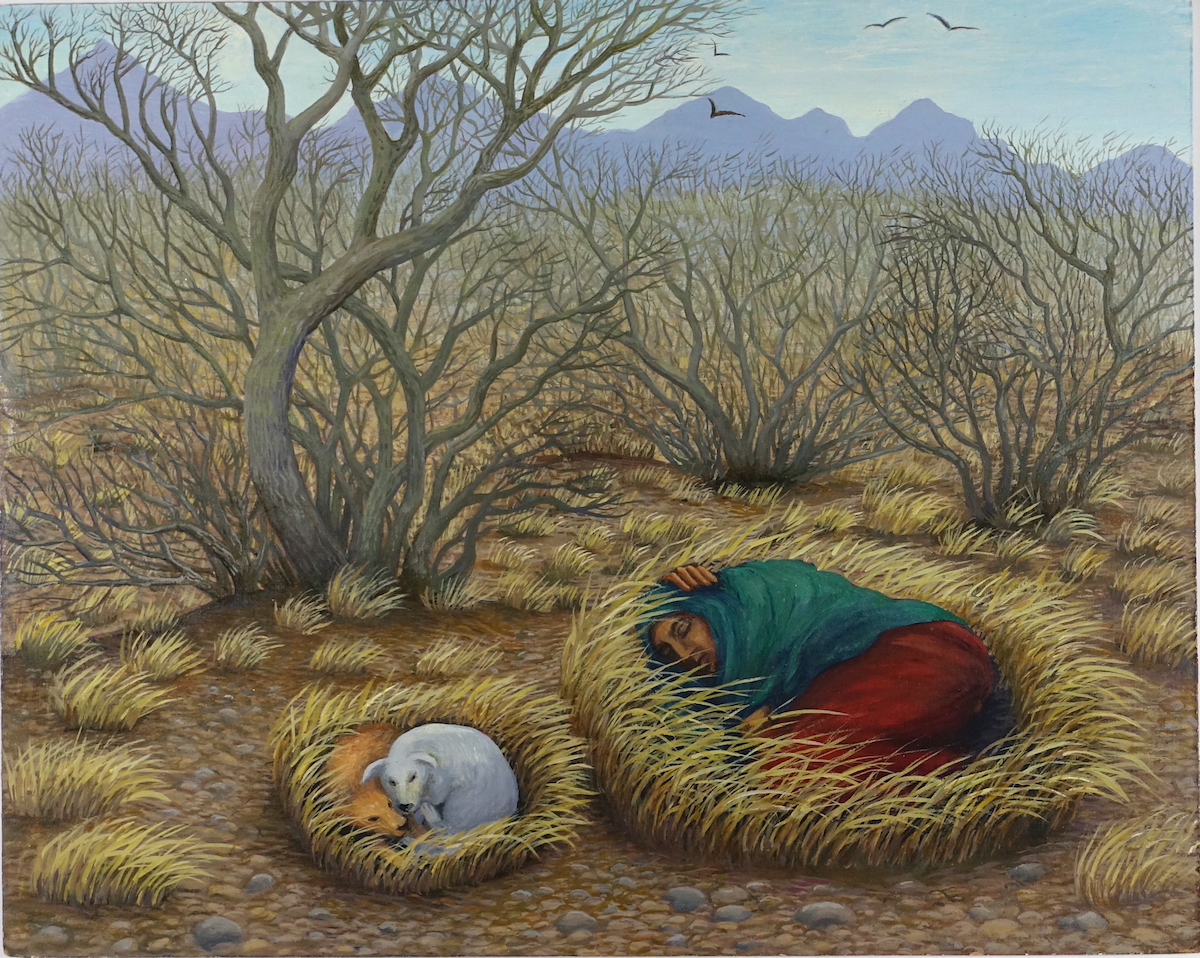

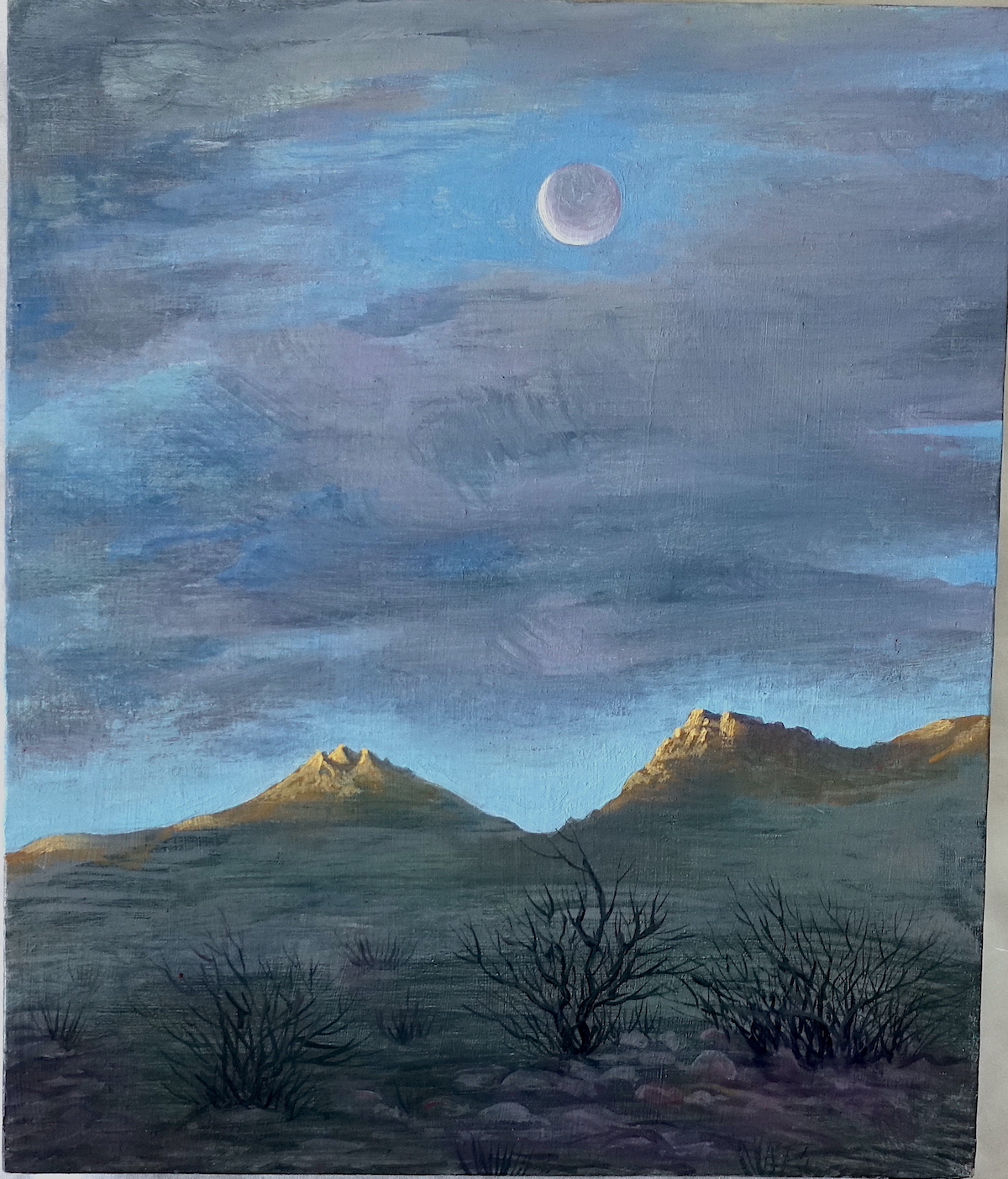

Reed is a painter, capturing the world around her, the desert of the San Simon valley beneath the Chiricahua mountain range where she has resided for the last 35 years. Her work also gives form to her dreams, which exist in another plane, neither here nor there but rather everywhere at once.

Environmental Transcendentalism is a conversation between the two artists, each struggling in their own way to find a path forward for humanity.

Nika Kaiser

In the past decade as hydrologists have studied Lake Powell the reality of climate change-impacted decline to water levels has already transpired, and the inevitable outcome is the reemergence of Glen Canyon from beneath its depths; the second largest canyon preceding the Grand Canyon which was carved by the Colorado River. In recent surveys of the lake, increasingly chalky calcified walls of the canyon stand starkly as maps of rapid evaporation, previously submerged trees and cacti are revealed as silhouettes shrouded in white silt, and remnants of trash from decades of recreational lake use are entangled in the arid deposits of the lake bed.

The Passage conveys an imagined future in which the past human, animal, and botanical elements of Glen Canyon reemerge from revealed slots in drowned canyon walls: marbled in red mud and white calcium, processing as reanimated, ghostlike forms in a re-destined reckoning of this simultaneously slow and rapid environmental disaster. The Passage offers ceremony for the loss of place and an implicit post-human future. Text excerpts from Gilles Deleuze’s Desert Islands offer suggested possibilities for the cyclical rebirth that exists in imminent dissolution.

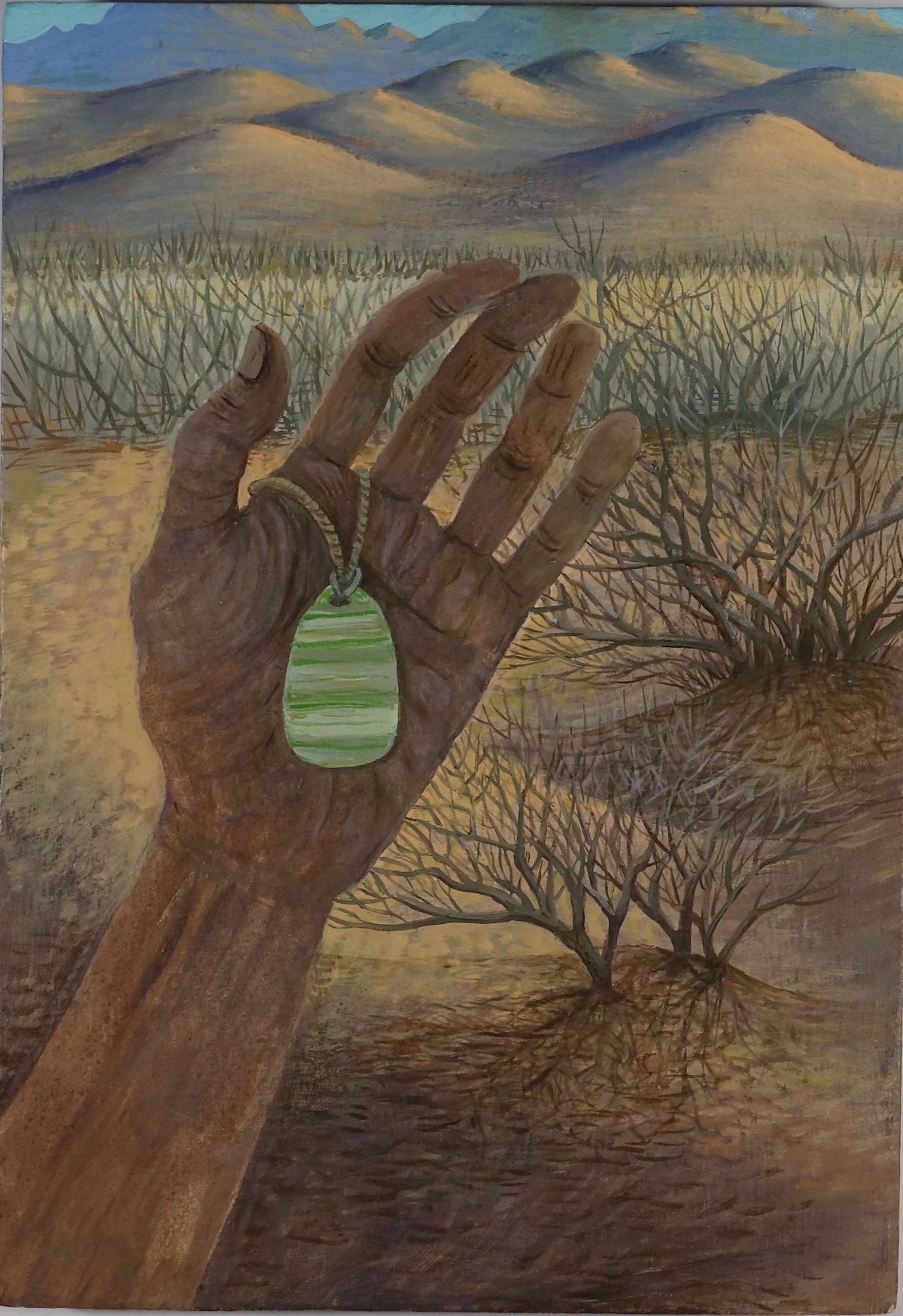

Celia Reed

Celia Reed paints what she sees and feels. Often there is a jagged line of purple blue mountains in the background, so you know where you are… on the land. In the foreground there may be a person or an animal, engaged in some solitary sojourn. Reed plays with the magic of light, so that you can feel the heat of sunlight radiating from the valley floor, or the magic of starlight in a dark and cooler sky. Half of her landscapes include the surrounding mountain ranges, the other half lowlands where the water pools. Where introspection happens.

Reed has always painted small canvases because the size suited her rustic lifestyle. Sometimes just wood, wrapping the painting onto the edges. The small size of her paintings increase the potency of what Reed sees. These paintings are focussed in a way that only a person who lives close to the land can show us.

There are a series of treasures, observed in her open hand. She shares her power with us. She challenges us to look deeply at what she wants us to see.

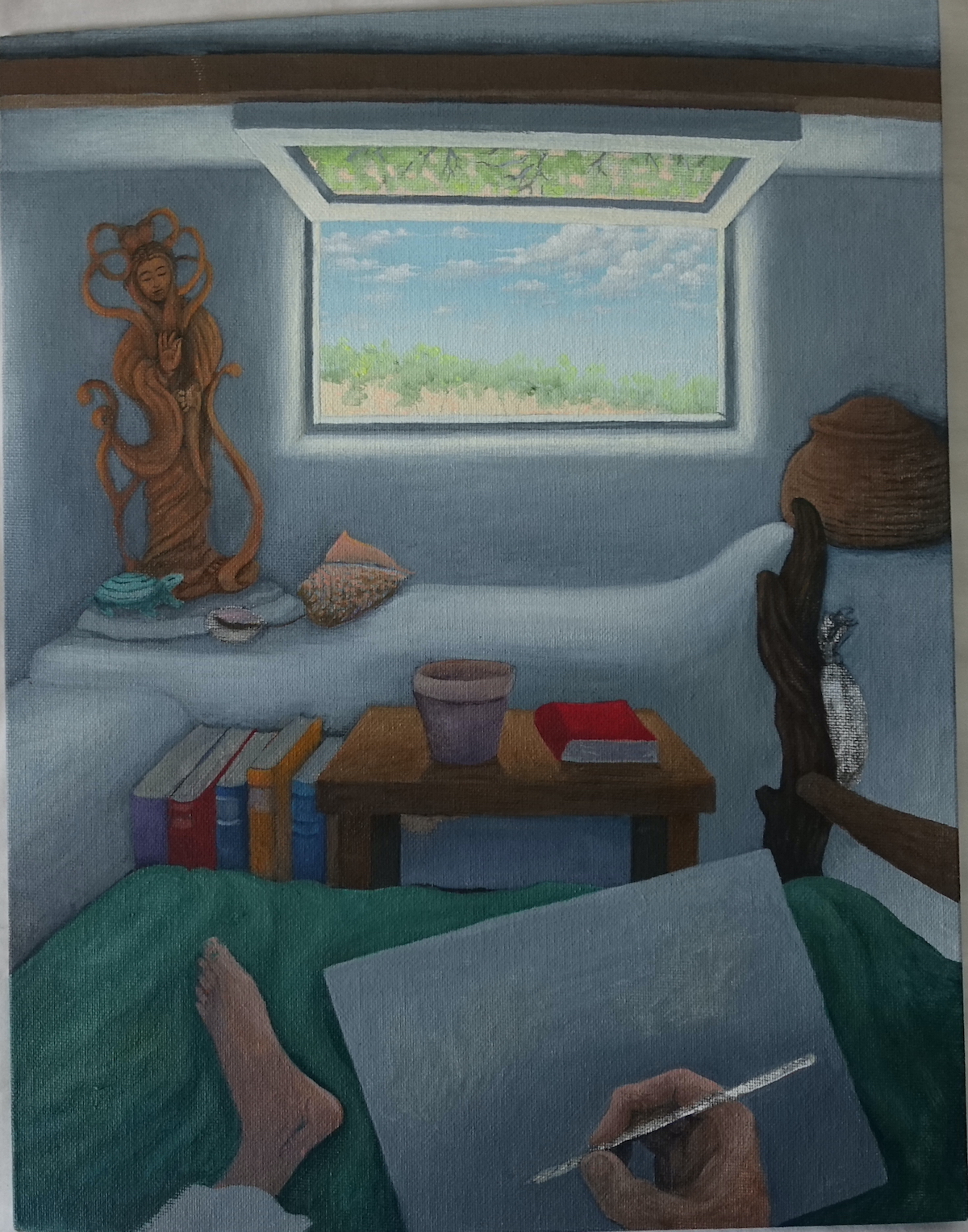

Then there are the interiors, all gentle and stately, with the stillness of really looking but also an exploration into the intimacy of light. Stillness and appreciation of a beloved inside space.

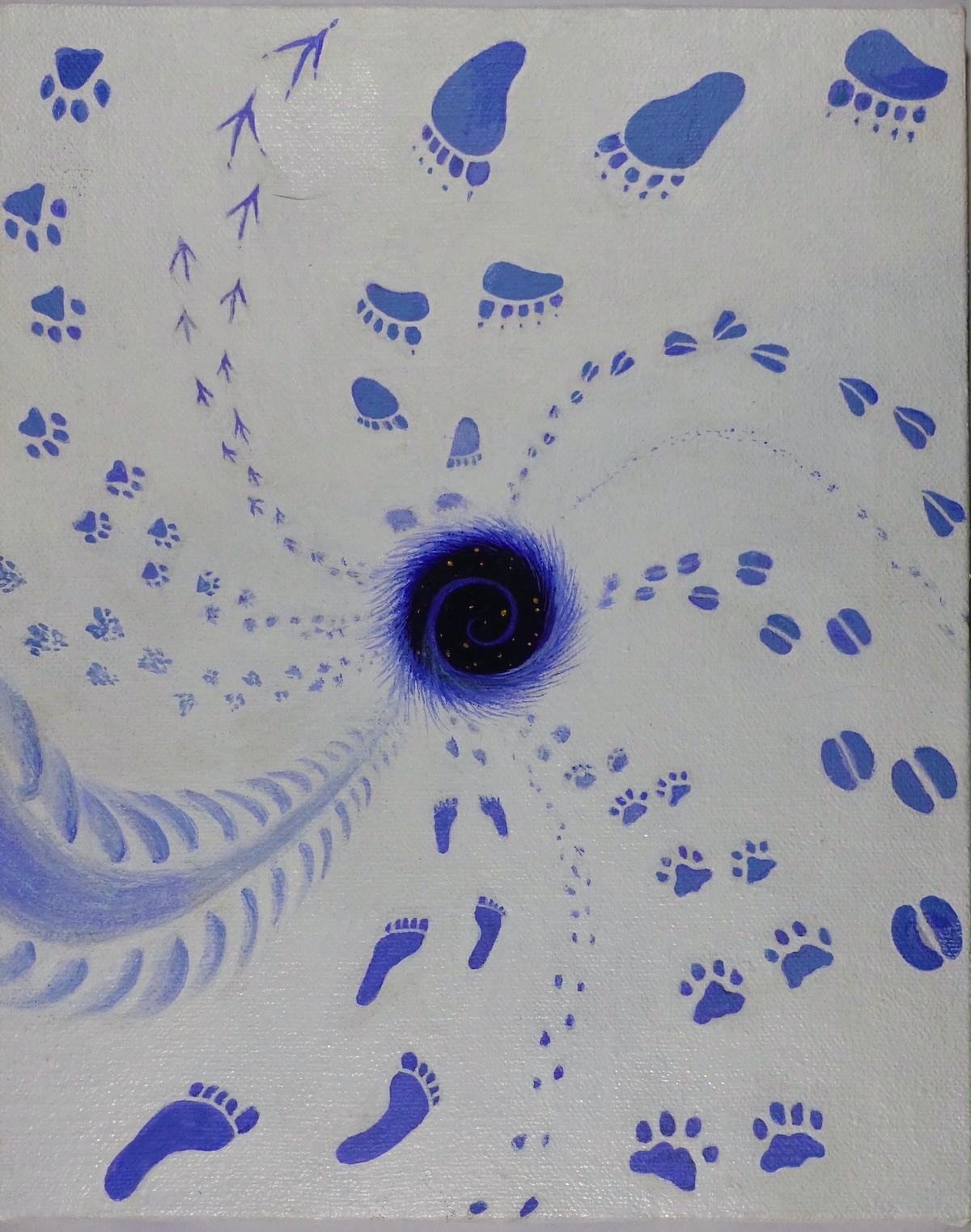

Last but not least are Celia’s dreams, inflated with windswept ferocity.

The past speaks to her, the animals speak to her and the land speaks to her; and she has made it so we can hear them by seeing her paintings. This is slow art– honest and illuminating.

Nika Kaiser

Nika Kaiser is a visual artist working with photography, video, and installation. Her art practice intersects ideas of mysticism, interspecies connection, and future ecologies.

Kaiser received her MFA in Visual Art from University of Oregon in 2013. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including shows at the American Institute of Thoughts and Feelings, Tucson, AZ; Bruce High Quality Foundation, Brooklyn, NY; Coaxial, Los Angeles, CA; Portland Museum of Modern Art, Portland, OR; Border Patrol, ME; Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, NY; University of Dubai, UAE; WNDX Festival of the Moving Image, Winnipeg, MB; Antimatter [Media Art], Victoria, BC; University of Rostock Museum, GE.

She has been the recipient of numerous awards, including two Arts Foundation New Works Grants and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Fellowship. She is an alumni member of the collective Ditch Projects in Springfield, OR and current member of the video collective Ungrund. Her photographs and videos have been featured in Wut Magazine, Azymuth (Spain), and on NPR. She teaches experimental practices in the Department of Film and Television at the University of Arizona.

Celia Reed

My Friend Celia

We met in 1980, in Santa Fe, and shortly after, moved together to a commune between Santa Fe and Taos, in a canyon leading up to the Truchas peaks, surrounded by magical pink hills dotted with Juniper. I took care of the pigs, goats and chickens, and Celia watered and looked after the Jerusalem artichokes we grew. When we parted ways we stayed in touch, mostly due to Celia’s devoted diligence to correspondence. Later she would write to me from Mexico where she and a couple of friends lived in caves among the Tarahumara. She eventually settled on the east-side slope of the Chiricuahua mountains near the town of Rodeo, about the same time I settled in Tucson.

First she built a classic pit house, which was eventually abandoned to the rattlesnakes.Then she built her own straw bale adobe house, as much as she could by her own hand. And she painted, always on small canvases. Her inspiration was in the land around her. It was a stark lifestyle, hauling water, heating with wood, no cooling during blazingly hot summers, very little electricity. Emphatically this was her choice, a primitive lifestyle in the Sonoran desert as a painter.

There she remained for the last 35 years. She does not own a computer or a cell phone. She harvests rainwater, a life depending on conservation. She made her peace with the rattlesnakes that invade every spring. She thrived on the drama of weather that unfolded around her, and relished her view of Pelloncillos peaks across the valley.

This show is her farewell now to her desert home, as she plans to return to her native England later this year. At 71, she will enjoy her sisters whom she has missed for many years, and perhaps get to know the generation of nephews and nieces who have grown up while she was away.

Each of these paintings are a reverential goodbye to the corners of her home, to the metates filled with rain water, to the transcendentalist dreams she puzzled out. These paintings are the footprints of 35 years spent in the desert.